These reflections arose a few months ago, while traveling back from FlexoDay South event of Atif, as I was telling colleagues-friends about my “adventure” in Africa.

Out of Africa

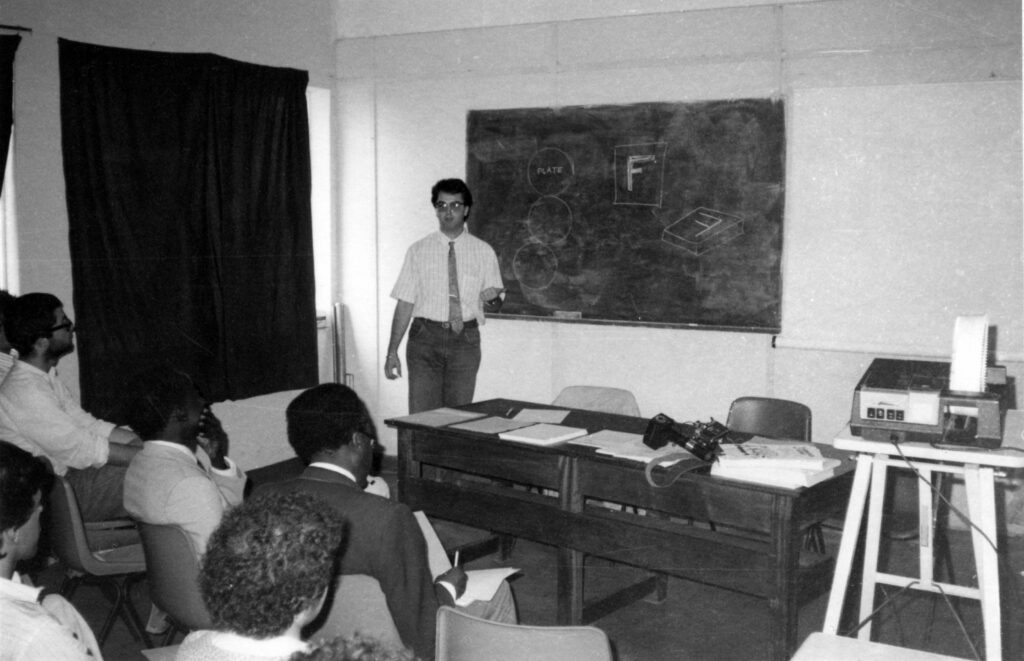

I arrived in Uganda in March 1987, almost fresh out of high school, involved as a volunteer in an Italian technical cooperation project in developing countries. The activity took place at the School of Media Development and Graphic Arts in Kampala, where I worked until the summer of ’89, and those years deeply affected my life, both personally and professionally.

Those incredible toys

One of the first things that struck me upon arriving in that country just coming out of a period of great internal unrest were the children’s toys. The little boys were not using a stick as a rifle to “play war,” but a set of pieces of wood and iron with the exact features of Kalashnikovs that, alas, they were probably already familiar with. Then there were those cars made of iron wire, which were “driven” with a stick by running barefoot in the red soil: they were not simple little boxes with four discs in lieu of wheels, but “real” Mercedes, Jeeps, Land Rovers, reproduced in their exact shape. And the same thing was seen in other toys, all with the features of the original objects that probably in the eyes of those children represented the technology, prosperity and modernity they lacked.

Reproduction and creation

What a difference with my childhood memories, where sitting in a cardboard box-car, or standing on a wooden board-jet, became driving a racing car with friends in fabulous competitions! It was as if in those Ugandan children the ability to create was limited to finding the pieces to build a toy of which they saw only the outer shell. They had the extraordinary ability to reproduce the “final product” with, to say the least, limited resources and incredible care in details, but something was missing… As if the imagination that at the same time connects and distinguishes imagination from reality, that “pretend” that goes beyond the real thing (the cardboard box) to develop the new, “playing” on the process (the rush into adventurous territories to win the race with their friends) did not come into play – in a proper and figurative sense.

Where there’s a will there’s a way?

Why all this nostalgia? Because every now and then (often) I get like déjà-vu that reminds me of those children’s games. This happens to me when I hear printers who “want” to achieve a goal – say: to print in expanded gamut – or who “need” to improve print quality, perhaps to maintain or regain a commercial positioning. And this happens when, frequently, the goal is more or less clear but there is a lack of clarity about the management of the process.

I mean that – sometimes even in excellent companies with great vision and development capability – there is a lack of awareness of how much expertise really matters in the processes where you want to introduce innovations. In short, I have met plenty of entrepreneurs and managers who set challenging goals and at the same time struggle to accept changes in work habits, in the setup of the printing system, in the level of training of the team involved in the production process. Plant/production/product managers who don’t “really” know how to manage color, who don’t know the foundations on which the graphic processes that give rise to our printed products are based.

Missing in many, many realities is that basic technical education that must be filled and continually perfected if we really want to change, innovate, improve.

Power is knowledge

As someone I can’t remember who it was used to say, “He who doesn’t know is forced to believe everything.” I would add for my part that “he who does not know how to do things, does not know how to change either”: it is not enough to decide what to do, you need to know how to do it.

This mentality, still so prevalent in companies, has multiple roots: in the history of Italian manufacturing, in the origins of the post-World War II economic boom, in the long-dominant idea in our humanistic-taught culture that “technical” is vile and, worse, is opposed to “artistic.”

These limitations, overcome by the evolution of reality but permanent by inertia in the widespread mentality, are compounded by those of technical and vocational schools, which are trying hard to fill those gaps that are so conditioning. The situation is well known. There are no printing presses in the institutes. I’m talking about “real” machines, the ones that those kids will see for the first time – if they are lucky – during their curricular internship, or only at the end of their studies, when they set foot in a company.

The curricula are being updated with great difficulty, held back by the retraining needs of the teaching staff themselves, who have to deal with such pathways on their own, and/or by the difficulty of establishing relationships between the school and the world of work.

We are aware, are we not, that we are talking about the people who will lead the industry in the coming years?

Not to mention in-company continuous training, always postponed for economic reasons and in any case seen as a cost rather than an investment that creates value…

Conclusions

If you have been paying attention, you will come to the conclusion yourself. In our world of “graphic arts” in order to make product innovation, to introduce new technologies, to envision new goals by overcoming the current state of affairs, one needs to really know, in detail, the mechanisms through which printing processes are carried out. It is necessary to bridge with a theoretical and in-depth technical explanation what cannot be seen and from which, not by magic, the quality of the printed matter, the rationality of the process, the added value that creates excellence and marginality are born. Because Art/Imagination/Creativity rest on Accuracy/Nature/Law.

Because “One need describe the theory, and then the practice. Those who fall in love with practice, without science, are like the helmsman who boards a vessel without a rudder or compass, and who never knows where he may be cast. Practice must always be built on good theory.”

[Of the error of those who use practice without science – Leonardo Da Vinci]